Climate change related litigation in Indonesia

Driving factors of climate change related cases in Indonesian court during 2010–2020

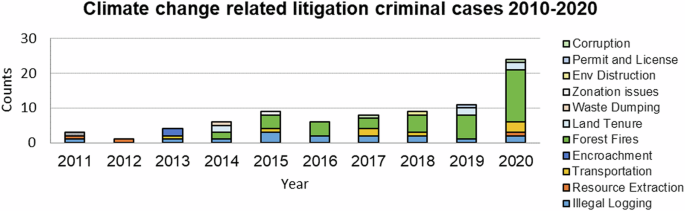

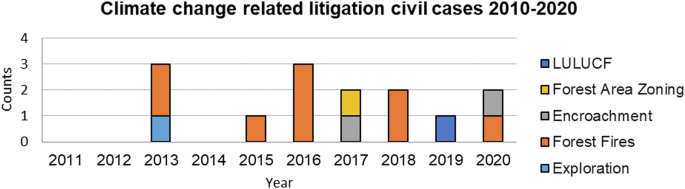

Climate change related litigation cases within the period of 2010 to 2020 are shown in the graphs above (see Figs. 1 and 2). This study discovered that this progress is attributable to several driving factors. Firstly, the development of science in climate change issues, such that litigants can use them as grounds for their claims. Consistent with Burger’s argument41, we have seen how climate change related litigation cases in Indonesia have been utilising scientific developments by: (i) introducing expert scientific testimonies and reports as evidence in criminal and civil cases to explain the causal links between GHG emissions and climate change; and (ii) challenging government failure to regulate GHG emissions in civil cases.

This figure shows the upward trend of climate change related litigation on criminal cases in Indonesian court during the period of 2010–2020.

This figure shows the trend of climate change related litigation on civil cases in Indonesian court during the period of 2010–2020.

Expert witness testimony has played, and continues to play, an important role in linking climate change science to the cases. In criminal cases, thirty nine out of eighty cases have included expert witness testimonies elaborating on the climate change implications of forest-related incidents. For example, in the Case No. 254/PID.SUS/2017/PN PLW (on illegal logging, verdict: guilty), the expert witness testimony stated that “ecologically, the Defendant’s actions can lead to the conversion of forest functions into plantation areas. Additionally, the damage to the Kerumutan Forest can result in the disruption of the ecosystem, climate, and the extinction of several wildlife species”. In the Case 140/Pid.Sus/2013/PN. PLW (on encroachment, verdict: guilty), the expert witness testimony highlighted, “the actions of the defendant, utilizing the Tesso Nilo National Park (TNTN) for palm oil and rubber plantations, are not in accordance with its designated function. This has led to the loss of TNTN’s ability to maintain its role as a flood control area, carbon dioxide absorber, oxygen supplier, and regulator of global climate, among other functions”. Here, we see the concrete link between the scientific evidence of climate change and climate catastrophe. In civil cases, two out of fourteen cases studied had expert witness testimonies featuring climate change considerations. This number is small, but it indicates that judges take into consideration climate science when adjudicating. Moreover, the remaining twelve cases featured climate change in their claims. These cases are listed in the Table of Cases-Climate Change Related Litigation 2010–2020 Indonesia (Criminal Cases), as Case no. 8 and no. 16 in the Supplementary Data 1, attached.

Out of fourteen civil cases studied, seven cases challenge the Government on the basis of their failure to regulate GHG emissions. Both local and national Governments were involved; requests were made to the local leaders (mayor or governor), or the Minister of Environment and Forestry to revise or revoke current regulations and any implementation efforts thereunder. In three cases, such requests were even aimed at the President of Indonesia. This shows how plaintiffs in these cases understand the importance of GHG emission reduction on mitigating climate change, and that enacting and implementing the relevant regulations forms part of the Government’s responsibility.

Secondly, the development of nexus between human rights and climate change, as litigants can use the link between their human rights issues to climate change impacts. In the international sphere, the nexus between human rights and climate change has been increasingly acknowledged. The preamble of the Paris Agreement specifies that parties ‘should when taking actions to address climate change, respect, promote and consider their respective obligations on human rights’42, and the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) had adopted 11 resolutions on human rights and climate change43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53. This development helps national and sub-national actors to easily link the effects of climate change to the fulfillment of human rights in climate change cases.

Specifically, climate change compromises the human right to life, right to adequate food, right to the enjoyment of highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, right to adequate housing, right to self-determination, right to safe drinking water and sanitation, right to work and the right to development43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53. In the cases examined in this article, we have seen arguments highlighting how environmental damage would lead to a deterioration of the quality of life of the people living in the affected areas. In deforestation cases, the argument most used in relation to the impact of climate change on human rights was that deforestation caused the forest to lose its water retaining capacity, consequently endangering access to clean water and/or a good quality of living. Although these links might seem obvious and simple, there is potential to explore their nuances and implications. Therefore, it is expected that as climate change related litigation continues to grow, so too will the nexus between human rights and climate change.

Thirdly, judicial training and certification on environmental law, so they know how to proceed with environmental cases. Indonesia had initially planned to establish an environmental court system54, but decided to install ‘green judges’ or ‘green benches’ in the general courts instead37. This demonstrates Indonesia’s aspiration to have regular court judges proficient in environmental issues11. Judges who have been trained in environmental issues are given an ‘environmental judges certification’ to certify their expertise in handling environmental issues. Furthermore, all environmental cases are tried with at least one certified judge55. However, as discussed, this training and certification needs to be amped up and pushed for as current statistics reveal that only 10% of judges in Indonesia have the environmental law certification11.

Fourthly, increased transparency and public pressures on climate change court cases. For example, the Indonesian Supreme Court started a website publishing all court documents on their website in 2011. As such, environmental cases can be accessed, read, and analysed by the public. Moreover, a new service had also been added to the Court’s website: an ‘e-Court’ wherein plaintiffs can register, get an e-summon, engage in e-litigation, receive an e-copy of the verdict, and e-sign documents.

Furthermore, Law No. 14 of 2008 on Public Information Disclosure obliges the Government to provide accurate information in timely manner to the public. Fulfilling this obligation thus requires the Government to provide facilities such as buildings or rooms for complaints, a complaint desk, and an online complaint network.

On top of that, public pressures from the civil society and environmental NGOs in Indonesia have been increasing. The number of environmental NGOs in Indonesia has grown immensely: there were 8720 in 1990 and this figure grew to 13,400 in 200056. Although there have been criticisms on the effectivity and transparency of these environmental NGOs, these NGOs are generally recognised and relied upon as watchdogs who monitor the government and court activities in relation to the environment and climate change57.

Lastly, government support and political will for climate change related litigation. The support can be in the form of moral and political support, where the government conferred the courts with legal authority to work independently, providing them with a sufficient budget, infrastructure, human resources, and security. In criminal and civil climate change cases, we saw that the government, especially the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MoEF), was extensively involved. In the criminal cases, we saw that the prosecutors often referred to MoEF reports and/or permits for evidence, or as expert witness providing testimony for the cases; in civil cases, the MoEF was directly involved as litigants, despite, as we had previously examined, how the GoI is adamant in pushing for the annulment of unfavourable verdicts through cassation and case review (peninjauan kembali). This shows conflicting governmental priorities in Indonesia. Indeed, climate change related litigation appears to be in tension with the governmental pursuit of economic development based on a carbon-intensive economic growth model, because it may upend the current political and economic system, the system that gave rise to the climate crisis in the first place14.

In terms of political will, environment and disaster resilience was listed as priority under Agenda 9 of the National Development Medium Term Plan (Rencana Pembangunan Nasional Jangka Menengah, RPJM) 2009-201458. Subsequently, the RPJM 2015–2019 listed not only environmental and disaster resilience, but also included climate change issues into the cross-sectoral development plan59. The latest RPJM 2020-2024 builds on the previous RPJMs and lists climate change as a priority and includes low carbon development within the agenda60. In addition, it should be noted that each RPJM explicitly highlights the development of equity and justice within the courts of Indonesia. Each of the RPJMs would list accomplishments of the last RPJM and include more ambitious goals, just like what we have seen with climate change issues. For example, abatement of forest fires was a priority within the disaster and climate resilient agenda of RPJM 2015–2019. As a result, Indonesia’s annual forest fires have been reduced by seventy-five percent from 1990 levels in 202061.

The roles of climate change related litigation cases in Indonesian courts

Even though these cases are incidental cases on climate change, this study argues that they hold important roles in the evolution of climate change issues in Indonesian courts. Their roles include firstly, opening a discussion on climate change in the Indonesian courts. Litigants, law enforcers, and the Courts have familiarized themselves with these issues because of these cases. These cases show that through the years, the inclusion of climate change as a claim increases the confidence of litigants.

Secondly, some of these cases (especially the civil cases) became popular and were taken up by national and international media. Media coverage brought attention to the cases and issues at hand, making the public more aware of the legal proceedings. The increased visibility led to greater accountability for the justice system, as the actions and decisions of judges, lawyers, and other stakeholders were scrutinized by a wider audience. Media coverage also contributed to a more transparent legal process, shaped public opinion about the cases and the parties involved, and introduced the public to the discourse of climate change in the courts. In broader terms, media coverage also influenced public trust in the justice system. Fairness and effectiveness of the legal process for these cases were shown in the open such that the public could directly see and build perceptions of the performance of the courts.

Thirdly, these cases can increase the social and political charges towards the Courts and the Government. With the exposure of climate change as an issue in court cases, aside from triggering social and political discussions, it can also lead to action and changes in laws, policies, or regulation related to the issues raised by these cases. As seen in Komari v. Mayor of Samarinda39 and Ari Rompas v Government Indonesia32, these cases had the potential to push the government to change the current regulations to the betterment of the climate and the environment. Even though both cases were rejected at the Supreme Court level, the discourse of climate change had already taken place in the country, and actions and changes had taken place in Indonesia. Many campaigners, public discussions, as well as books and research reports pushed the government of Samarinda and Palangkaraya to upgrade their policies and regulations for the betterment of the climate and the environment. These cases built a bridge for more ‘core’ climate change litigation cases in the Indonesian judiciary.

Overall, these results demonstrate the complexity of climate change related cases in Indonesia. Nevertheless, there is improvement from the fact that law enforcers and litigants are using climate change as a basis for their claims. This shows that the issue of climate change has been accepted as increasingly important, to the extent that it is accepted as an argument in court, and possibly beneficial one at that. Indonesians are fully aware of their own rights and obligations and understand that it is the responsibility of the State to protect these rights, including the human right of being safe from the threats posed by climate change. This might be the dawn of the new beginning for the future of ‘core’ climate change litigation in Indonesia. Further research needs to be done in other jurisdictions, to see whether this situation of incidental climate change cases exists and are playing vital roles to give opportunities for more ‘core’ climate change litigation cases to thrive.